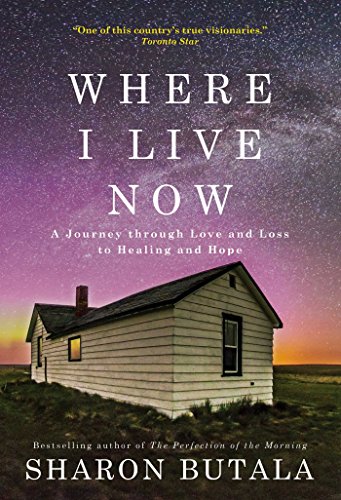

Items related to Where I Live Now: A Journey through Love and Loss to...

“It was a terrible life; it was an enchanted life; it was a blessed life. And, of course, one day it ended.” —Sharon Butala

In the tradition of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, Diana Athill’s Somewhere Towards the End, and Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal comes a revelatory new book from one of our beloved writers.

When Sharon Butala’s husband, Peter, died unexpectedly, she found herself with no place to call home. Torn by grief and loss, she fled the ranchlands of southwest Saskatchewan and moved to the city, leaving almost everything behind. A lifetime of possessions was reduced to a few boxes of books, clothes, and keepsakes. But a lifetime of experience went with her, and a limitless well of memory—of personal failures, of a marriage that everybody said would not last but did, of the unbreakable bonds of family.

Reinventing herself in an urban landscape was painful, and facing her new life as a widow tested her very being. Yet out of this hard-won new existence comes an astonishingly frank, compassionate and moving memoir that offers not only solace and hope but inspiration to those who endure profound loss.

Often called one of this country’s true visionaries, Sharon Butala shares her insights into the grieving process and reveals the small triumphs and funny moments that kept her going. Where I Live Now is profound in its understanding of the many homes women must build for themselves in a lifetime.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Often as I lie down in my bed, pull up the covers, and put out the light, settling in to spend another night alone here in Calgary, Alberta, I yearn to have my husband, Peter, with me again. I yearn not to be alone. But that is an old story, and among people in the last third of their lives, it is anything but unique. But, still, I lie at night and think of the past. I dream of it too — our life on the Great Plains to the east — and when I do, I wake filled with sadness. Once in a while a tiny part of me will for an instant take me over, allowing me to imagine there is a way to regain the past, but then reality returns, and my inner voice says, You know as well as you know anything on earth that he is gone forever. And yet, I am not sure I truly believe it.

I try to visit my husband’s grave at least once a year, sometimes twice a year, although never in winter. When Peter died, I thought that as I wouldn’t be able to keep on living in Saskatchewan, I would be faithful about my twice-yearly visits to his grave for at least the next ten years; after that, my imagination gave up. Some part of me probably thought that in ten years I would most likely be dead myself. When I imagined my own demise I could only think in terms of statistics. I stopped short when it came to the nursing home, the fatal illness, the final suffering, my last, shuddering breath.

When I make my private pilgrimage, I don’t let anyone know I am coming. It takes about seven hours from Calgary, including at least a half hour to get out of the city and another for fuel and bathroom stops, and I need to stay overnight before I make the long drive back. When I start from Calgary I am filled with determination to complete what I see as my duty to Peter (as if he were still alive and monitoring my faithfulness), and I do my best not to think but only to concentrate on the traffic and the road, but all the while some strong emotion is building inside me. I drive the first three predictable hours (farms mostly, or fields of grass, usually pretty heavily grazed, a few head of cattle in the far distance, oil batteries, railway lines) on the high-speed, busy Trans-Canada Highway to Medicine Hat, where I make my usual stop to stretch my legs, buy gas, and buy food to take on the road with me.

Then I continue east, and about an hour after having crossed into Saskatchewan, I turn south toward Maple Creek, go west through the town and onto the secondary highway heading south. Here I am able to go more slowly, as the road narrows and the speed limit drops. Finally, almost no one else is on the road; I can take my time as I drive through the familiar, once much-loved countryside. Now I can no longer fully control the emotions I’ve been keeping at bay. They begin to grow and rise and will soon threaten to overwhelm me.

Something like eighteen miles south of the town, having climbed most of the way, I reach the gate into Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park, but for some miles before, I can see the park along the horizon on the western side of the road. It is easily recognizable because in a landscape where most of the year the fields and hills are the pale yellow and buff of cured grass, its high, pine-covered hills, dark blue-black with hints of deep green, stand out. In a country otherwise sparsely treed except for the deciduous ones planted in neat rows by settlers in their farmyards, the attraction of these immensely tall, though thinly limbed, lodgepole pines in a park that is the highest point between the Rockies and Labrador is understandable.

The park rises about 2,000 feet (600 metres) above the high plains, and stretches from Saskatchewan into Alberta. It is treed as a result of the glaciers having spared the highest part; here montane species of plants still grow that occur nowhere else in the province. From sea level, the highest point is in the Alberta portion of the Cypress Hills and is roughly 4,800 feet; in Saskatchewan, it is about 4,500 feet. It’s only when you get to the Lookout on the far west side of the park that you see how high you are.

On these trips I rarely pass by the gate without driving in, and sometimes, if I’ve thought to buy a lunch in Medicine Hat, I may find a picnic table somewhere and eat my sandwiches under the trees, my feet resting on grass instead of a sticky restaurant floor, and my head filled with pine scent and the cool, fresh, welcoming air hinting of the wild. I was born in the forested, lake-dotted country to the north where such vistas are commonplace, and I find these pines a welcome break from the miles of treeless, anonymous country I’ve just come through. I often contemplate how strange it is that I fell so in love with a terrain and ground cover so completely different from the one I was born into and where I first knew life.

I often think that my sisters and I came out of legend. Our childhood in the northern bush is so linked with fear — of the extreme cold and deep snow, of the dark trackless forest all around us, of the Indigenous peoples who had their own ways, who did not speak our language, indeed, who rarely spoke — that I chose as a writer to turn my beginnings into a dark myth. I saw too the paucity of the conditions under which we lived, our mother’s youthful gaiety slowly overtaken by disappointment and anger, our father’s bewildered, helpless retreat.

When I was just school age we left that part of the country forever, moving gradually to larger towns and then to a small city. I tried to forget the wilderness, believing then that people could forget where they began, as if it were merely a mistake. But I know now that our childhoods mark us forever, and that to view such happenings in a life as mere mistakes, as simple bad choices, is in itself a mistake. Where we start life marks us irreparably. More than twenty years later, a marriage, a child, a divorce, and moves across the country and back again behind me, at thirty-six I married Peter and went to his ranch home in Saskatchewan on the high Great Plains of North America to live out the rest of my life. And yet, that archetypal forest I was born into hovered there relentlessly, dark and heavy, in the back of my brain. Cypress Hills Park, then, has seemed only to hint at that forbidding landscape from my childhood.

I sometimes take the time to drive up to the highest point at the Lookout where, in three directions and a few hundred feet below, I see fields and more fields, sprinkled with grazing cattle, mere dark points on the pale aqua, buff, and cream grass, the colours exquisitely softened by distance and haze until at some far-off edgeless place they simply meld into the pale bottom of the sky, become indistinguishable from it. The wind catches you up there, sweeping across miles of prairie and smelling of burning sun and grasses, sage and pine, and flowering bushes. The far-distant world below that I’m scrutinizing is, from this vantage point, fairy-tale beautiful, and it is a wonder to me that the society it supports should sometimes be so unforgiving, so brutal to its dwellers.

Although from where I was in the park I couldn’t see it, a few miles to the east in the wooded hills on the other side of the highway, still part of the Cypress Hills, is the Nekaneet First Nation. It would be many years after I moved to the southwest before I would even set foot on the reserve itself and then it was, briefly, to volunteer at the new Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge, a prison for federally sentenced Aboriginal women where I and a number of other farm and ranch women were to provide some “normalcy” in the lives of those women, some of whom had been incarcerated many years, and others who would soon be released to go back into society. I think the idea was that we would remind them of how to be with women out in general society. I also taught a creative writing workshop, where I wound up mostly dealing with the single white woman prisoner there, about whom, after she was released and died of ALS, a film was made. The other prisoner I saw the most of was a Cree woman, one who had collaborated as a co-author in a book about her life. I never thought of them as prisoners, though, but rather as people I knew and liked (both had committed murders, although the white woman would eventually receive a special dispensation and be released early as a victim of severe marital abuse). I would have kept them both as friends had the justice system allowed such a thing, and if one hadn’t died so soon after her release.

It is told that when a site for the lodge was being searched for, a committee of elders was struck, and one of them had a dream telling all of them that this was where it should be built — in the place they called the Thunder Breeding Hills. It is gratifying to think that is how the site was chosen. When I first saw the reserve, appearing as a horizontal white line high in the treed hills miles south of Maple Creek that, as you drew closer, would separate into buildings, it was poor and barely known by most of the local people unless they had land near it. The relationship of the townspeople to the people of the reserve seemed to me then fraught with tension and, to some extent, mutual dislike and mistrust. Then the people of the reserve had their land claims settled, and exciting things started to happen, the building of the healing lodge being only one of them.

Once, these people travelled all over this vast land, without any barriers or park signs or jails, following their ancestral trails. As the settlement era began in the West in the late 1800s, treaties between the European newcomers (many from Eastern Canada and the United States) were signed that drove Indigenous peoples of the plains onto small reserves. Treaty 4, signed in 1874, moved them south of the South Saskatchewan River, to the north, or east of the city of Regina. Only a small band of people led by a man named Nekaneet (or “foremost man”) remained behind in the Cypress Hills, living on game and otherwise making do for many years until in 1913 the government granted them a small reserve in the hills, later expanded. The rewards of signing these treaty documents were laughable, and in the late twentieth century such high-handedness and injustice to the First Nations people were at last addressed in the form of land claims designed to return much of the ancestral lands to the descendants of the original inhabitants. The Nekaneet people didn’t receive the right to be included in the land claims process until 1998.

South I go now, until I come to the gravel road that threads its way east and south to the village of Eastend. With some regret I pass it by. On these drives to visit Peter’s grave, I rarely take that cross-country route, even though it cuts about twenty miles from the already long trip. On my move to the city, I sold our large SUV, opting instead for a more manageable small car, the first vehicle in my entire life that I had bought myself. Inexperienced as I was, I didn’t notice that its clearance was too low to allow me to risk gravel roads, so on these trips to Peter’s grave I usually go around the long way on the paved roads. The drive descends most of the way, the hills rising up on my left or to the east. If you know where to look, you can see cairns and other more enigmatic stone structures made by the First Nations people in past centuries, some of them visible as small protuberances along the skyline.

About forty miles south of Maple Creek, never having left a paved road, I turn east again on the highway into Eastend. In those first years after I moved away, my heart would start to ache as I left Medicine Hat, as I have told you. I would feel as if my chest and throat were filling with dark water, making an aching lump of them. Once I turned to go south at Maple Creek the pain would worsen, the water struggling to erupt from my eyes. When I made that last turn east to start the thirty-five or so miles into Eastend, I would be in full-blown pain, anger tinged equally with bitterness, bitterness that I otherwise kept at bay, but that never failed to overtake me as I neared my husband’s grave. Now the tears are gone, although a residue of pain remains.

Deep in the south country, heading east, on my right and another twenty miles to the south, lies what has been since 1910 or so the vast Butala cattle ranch. I can’t actually see it from that distance, because those many hectares of low rolling hills characteristic of the area intervene. But I know it is there, and think of the many times I had looked out the cracked kitchen window (a window Peter told me his mother had, years earlier, importuned her husband to put in because she felt cut off not being able to see in that direction) and gazed north, imagining trucks driving east or west on this very road. Sometimes, Peter said, on a really clear night, there would be places between the hills where from the ranch, there being not a single dwelling between the kitchen and the road twenty miles to the north, you could see the headlights of a vehicle. I’d seen one myself, that moving light travelling like a tiny spaceship through the darkness below the millions of stars.

This is when the longing I’m experiencing — or maybe it isn’t longing, as I don’t quite allow myself to long — this is when the pain and sorrow I’m experiencing are at their worst.

My emotions are so mixed I hardly know what to make of them myself; I only know they make me feel badly enough to want never to make this trip again. On the one hand, I suffered from extreme loneliness for many years in this country. On the other hand, the beauty of the land, the peace and simplicity of the life, even the roughness, and the doing without (high culture, congenial companions, a bathroom!) taught me a lot. Above all, there was the joy of being someone’s partner in life, someone for whom and from whom there was respect and love. This is the turmoil I experience every single time I make this trip. I suppose Joan Didion would call it grief, but it is, in fact, so much more than that. And who knows what Didion experienced that she chose not to put into The Year of Magical Thinking, her celebrated memoir about the year that began with her husband’s sudden death. Didion is, as Peter was, famously cryptic, famously silent.

A few miles past the place where I turned east, I come to the cattle gate that leads into the provincial pasture, a one-hundred-section area (a section is a mile by a mile), I think the biggest in the province, that borders on the west and the north of what had been the Butala ranch. I can’t see the gate from the road I am on, only the trail off the road; on the other side of a low rise you will bump over the cattle gate and then be in the pasture, and if you know which trail to take and keep going, winding in and out around the grassy hills, leaving the trail in places where rain or melted snow has made it impassable for twenty or fifty feet or, in wet springs, maybe even longer distances, going through other gates, past waterholes or large troughs where the water was pumped up by windmills or, in later years, by solar panels, with cattle clustered around them, eventually you will reach the gate that opens onto the Butala land less than a mile from the house. But you’d be a fool to try it if you didn’t know the country, and if it had been raining and you didn’t have four-wheel drive and a lot of experience driving under such condi...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2017

- ISBN 10 1476790485

- ISBN 13 9781476790480

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages192

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Where I Live Now: A Journey through Love and Loss to Healing and Hope

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.62. Seller Inventory # 1476790485-2-1

Where I Live Now: A Journey through Love and Loss to Healing and Hope

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1476790485

Where I Live Now: A Journey through Love and Loss to Healing and Hope

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1476790485

Where I Live Now: A Journey through Love and Loss to Healing and Hope

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1476790485

Where I Live Now: A Journey through Love and Loss to Healing and Hope

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1476790485