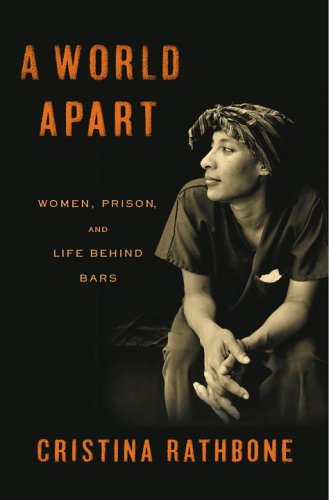

Items related to A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

The picture that emerges is both astounding and enraging. Women reveal the agonies of separation from family, and the prevalence of depression, and of sexual predation, and institutional malaise behind bars. But they also share their more personal hopes and concerns. There is horror in prison for sure, but Rathbone insists there is also humor and romance and downright bloody-mindedness. Getting beyond the political to the personal, A World Apart is both a triumph of empathy and a searing indictment of a system that has overlooked the plight of women in prison for far too long.

At the center of the book is Denise, a mother serving five years for a first-time, nonviolent drug offense. Denise’s son is nine and obsessed with Beanie Babies when she first arrives in prison. He is fourteen and in prison himself by the time she is finally released. As Denise struggles to reconcile life in prison with the realities of her son’s excessive freedom on the outside, we meet women like Julie, who gets through her time by distracting herself with flirtatious, often salacious relationships with male correctional officers; Louise, who keeps herself going by selling makeup and personalized food packages on the prison black market; Chris, whose mental illness leads her to kill herself in prison; and Susan, who, after thirteen years of intermittent incarceration, has come to think of MCI-Framingham as home. Fearlessly truthful and revelatory, A World Apart is a major work of investigative journalism and social justice.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

FLOSS

FLUFFY WAS A surprise. An aging seventies throwback with piles of teased blond hair and too much makeup, she was older than Denise Russell, past her prime perhaps, and sad, but not frightening, not threatening at all. Denise had never been in prison before. Thirty-two years old, with long dark hair, high cheekbones, and the kind of body that only rigorous exercise can maintain, she’d expected to be confronted by the kind of crazed and violent criminals she had always seen portrayed on TV. But Fluffy had been helpful when Denise first moved into her cell. Motherly almost. She had explained, if in a sometimes showy, desperate way, how Denise should store her papers and valuable canteen snacks in the lockable one-foot cubby, and how to climb up onto the top bunk by straddling the pull-out chair and then leaping onto the corner of their shared metal desk. Originally designed for one, the ninety-square-foot cells had long served as doubles. There wasn’t enough room for a ladder.

Every once in a while Fluffy did manage to startle Denise with a sudden burst of frantic exuberance. She sang hippie love tunes off-key and belly-danced around their cell and out onto the unit itself, down the corridor to the officer’s glass-walled office, or “bubble” as it was known, and around the airless dayroom. Most of Fluffy’s time, though, was spent lying around on her bunk, watching soap operas and dreaming of her triumphant return to Han Lan’s, the divey Chinese restaurant where she’d ruled the roost before being sent away on a three-year mandatory for drugs. Her stories about the place were long and often dull, but as long as Denise indulged them the two managed to share their cell with relative ease. Fluffy was kind, that was the thing. Open-hearted. Denise had known women like her all her life.

Life in a women’s prison was full of surprises like this. Not that MCI-Framingham was a pleasant place to be. The housing units were crowded, dark, and noisy, and the aimless vacuum of daily life there often made you want to curl into yourself on your thin little bunk up close to the ceiling and cry. But it was nothing, nothing like Denise thought it would be. There were the locks, of course—including, most impressively, the one to her own cell—to which she would never hold a key. And there were the guards and continually blaring intercoms, which controlled the smallest minutiae of her everyday life. There were full, bend-over-and-cough strip searches both before and after a visit, and random urine checks, and cell searches, called raids, which left her prison-approved personal items (mostly letters and drawings from her son, Patrick) scattered all over the floor. She’d heard there were punishment cells too. Dismal, solitary cages with nothing but a concrete bed and a seatless toilet, to which women sometimes disappeared for months.

Despite all this, Framingham seemed more like a high school than a prison. Some of the guards were rougher than teachers would ever be, of course. Dressed in quasi-military uniforms and calf-length black leather boots, a few also flaunted their power, making irrational demands simply because they could. For the most part, though, Denise found it easy to keep out of their way. No, it was the inmates, not the guards, who reminded her of her days at Wecausset High—as did the unfamiliar experience of being with so many women. Framingham girls were older, and so lacked the freshness that graced even the plainest girls back at Wecausset. They were tougher too. Some had scars stretching across cheeks, jagging up from lips, or curved around their necks. Others, when they smiled, revealed the telltale toothlessness of crack addiction. But the overwhelming majority were mothers, as well, their walls decorated not, as she’d imagined, with images of muscle-bound men but with photos of their kids and sheets of construction paper scrawled over with crayon—valentines and birthday and Christmas cards saved year after year.

There were some unsavory types, and a smattering of women who seemed plausibly threatening. But even the handful in for murder looked more defeated than frightening. Most were long-term victims of domestic abuse who had killed their spouses, and though one or two of them did have an unnerving deadness to their eyes, they pretty much kept to themselves. Lifers, like everyone else at Framingham, were a cliquey lot, by turns supportive and undermining in the manner of, well, high school girls. As a group, they sat firmly at the top of the hierarchy—no matter how meek they appeared, they were, after all, in for murder—while the real social maneuvering took place in an ever-shifting universe of less powerful cliques beneath them.

There were the popular girls, who tended to be prettier than the rest and confidently rule-abiding at Framingham; the repeat offenders; the “intellectual” college crowd; the rabble-rousers; the hard workers; the butches; the femmes; and the group of untouchables—baby beaters mostly—whom nobody wanted anything much to do with. Most of these groups were self-segregated along racial lines, but those in parallel ranks often intermingled. Popular black women like Charlene Williams, a mother serving fifteen years for her first (nonviolent) drug offense, spent a lot of time with Marsha Pigett, a striking redhead and longtime victim of domestic abuse who was also in for drugs and who pretty much ran, for a time, the popular white set. The language barrier often made things more difficult for what everyone called “the Spanish women,” but they too were measured and graded and sorted into type, and a handful of Dominicans, Central Americans, and, separately, Puerto Ricans shared the ability to break free from stereotype and mix it up with the in crowd.

At first, none of this was clear to Denise. For months she could not tell the difference between a potential ally and a troublemaker when they stood next to her in line for meals, or for count, or for what they called “movement,” which were the only times in the day inmates were allowed to walk from one area of the prison to another. Besides, she wasn’t that interested. She didn’t belong there, she still believed. It was just as good to subsist quietly in the small shadow cast by Fluffy and to cradle there as much of her old life as possible.

But roommates are just one of the myriad things over which inmates have no control. While violence is the main concern in a male prison, at Framingham it is the creation of intimacy that most worries the authorities. For this reason, the population is kept fluid. Women are not allowed, officially, to hold the same job for more than six months, and roommates are routinely moved around.

So it was that one day Fluffy was gone, replaced by an elderly, drug-addled woman, the kind who steals extra chicken from the dining hall by hiding it in her bra, and who then pulls it out sometime later in the day to eat in her cell. Her name was Sonia, and like so many women in Framingham, she was a heroin addict serving time for drugs. Sonia’s age made her seem more damaged than most—she was old and worn both inside and out. Denise tried hard to be nice at first, leaping to her feet to help like the obedient grandchild she had, in fact, always been. But after a couple of weeks Sonia’s fragility began to wear her down and the reality of her own powerlessness in prison began, at last, to congeal.

IT HAD TAKEN a surprisingly long time for this to happen. The first few weeks had been terrible, of course, frightening and degrading and completely unnerving. “Just try to imagine it,” she told me. “Everything was gone. My son, my home, my family, my car, my friends, my cigarettes, my alcohol, my drugs, my clothes, my makeup, my dishes, my paintings, my socks, my glasses, my bills, my life—not to mention my dignity and my self-esteem (which wasn’t much anyways) . . . everything.”

She could see, however, that in a way the shock and anxiety of it all had protected her back then too. One minute she’d been at home, packing her son Pat’s brand-new Nintendo and his smart new clothes into the case he’d bring with him to her mother-in-law’s house, the next she was inmate number F24447, being stripped naked, checked for STDs, and asked if she felt depressed by someone in a uniform on the other side of a desk. This last question seemed the cruelest of all because it wasn’t as if she cared, the nurse or whoever she was. She didn’t even look up from the checklist in front of her when she asked. And how was Denise supposed to feel anyway, facing five years and a day in this place?

She cried all night, every night, that first week. She didn’t know, yet, how expensive collect-call rates were from prison, so she spent hours on the phone with her mother and her son, and endlessly marched around the yard, the headphones of her prison-bought Walkman tuned to heavy metal because she knew enough, even then, to stay away from anything in the least bit emotional. It only made her cry.

Then, two weeks after she’d arrived in August, just as her fixed daily routine had begun to numb her, three correctional officers unlocked the door to her room in the middle of the night. “Denise Russell? Denise Russell?” they asked, shining their flashlights in her face, so that even before she was fully awake, she knew something terrible had happened.

Silently the officers escorted her down linoleum-tiled corridors and through clanking metal doors to the Health Services Unit. There a nurse asked her to sit down, then told her that her son had just threatened to kill himself. He’d walked into her mother-in-law’s living room with a knife, she said. They needed her permission to have him admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Pat was her little just-nine-year-old boy, and right then he was in the admitting room of a state-run psychiatric hospital up in...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 1400061660

- ISBN 13 9781400061662

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages304

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1400061660

A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1400061660

A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1400061660

A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1400061660

A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1400061660

A World Apart: Women, Prison, and Life Behind Bars

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1400061660

A WORLD APART: WOMEN, PRISON, AN

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.1. Seller Inventory # Q-1400061660