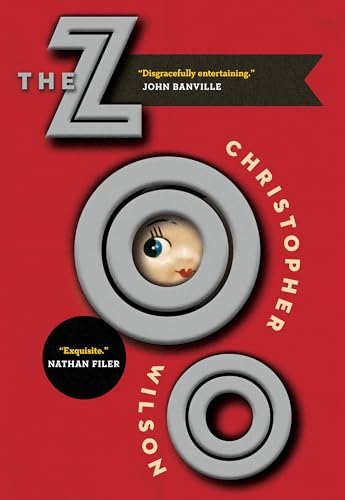

Items related to The Zoo

Patrick deWitt meets Catch 22, when a guileless young boy gets mixed up in Stalin's inner circle.

There are certain things that Yuri Zipit knows:

1. That being official food-taster for the Great Leader of the Soviet Union requires him to drink too much vodka for a twelve-year-old.

2. That you do not have to be an Elephantologist to see that the Great Leader is dying.

3. Yuri's father is somewhere here in the Dacha.

4. It's a crime to love your family more than you love Socialism, the Party or the Republic.

5. That, because of his damaged mind, everyone thinks Yuri is a fool.

But Yuri isn't. He sits quietly through excessive state dinners and witnesses it all--betrayals, body doubles, buffoonery. He's starting to get the hang of this politics thing, but there's so much to learn. Who knew that a man could be in five places at once? That someone could break your nose as a sign of friendship? That people could be disinvented?

The Zoo is a cutting satire, told through the refreshing voice of one gutsy boy who will not give up on hope.

There are certain things that Yuri Zipit knows:

1. That being official food-taster for the Great Leader of the Soviet Union requires him to drink too much vodka for a twelve-year-old.

2. That you do not have to be an Elephantologist to see that the Great Leader is dying.

3. Yuri's father is somewhere here in the Dacha.

4. It's a crime to love your family more than you love Socialism, the Party or the Republic.

5. That, because of his damaged mind, everyone thinks Yuri is a fool.

But Yuri isn't. He sits quietly through excessive state dinners and witnesses it all--betrayals, body doubles, buffoonery. He's starting to get the hang of this politics thing, but there's so much to learn. Who knew that a man could be in five places at once? That someone could break your nose as a sign of friendship? That people could be disinvented?

The Zoo is a cutting satire, told through the refreshing voice of one gutsy boy who will not give up on hope.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

CHRISTOPHER WILSON is the author of novels including Gallimauf's Gospel, Baa, Blueglass, Mischief, Fou, The Wurd, The Ballad of Lee Cotton, and Nookie. His work has been translated into several languages, adapted for the stage and twice shortlisted for the Whitbread Novel Award.

Wilson completed a published PhD on the psychology of humour at LSE, worked widely as a research psychologist and semiotic consultant and lectured for ten years at Goldsmiths, University of London. He has taught creative writing in prisons, at university and for The Arvon Foundation. He lives in North London.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Wilson completed a published PhD on the psychology of humour at LSE, worked widely as a research psychologist and semiotic consultant and lectured for ten years at Goldsmiths, University of London. He has taught creative writing in prisons, at university and for The Arvon Foundation. He lives in North London.

Call me Yuri. Though I get called lots of names, such as Yuri nine-fingers, Yuri the Confessor, or Yuri the Deathless. But my full, formal title is Yuri Romanovich Zipit.

I am twelve-and-a-half years old and I live in the staff apartments, in The Kapital Zoo, facing the sea-lions’ pool, behind the bisons’ paddock, next to the elephant enclosure, and I like to play the piano but I am no Sergei Rachmaninov because my right arm is crooked and stiff, so I mostly play one-handed pieces, such as are written for the army of one-armed veterans, who sacrificed a limb for the Mother-land, fighting in the Great Patriotic War.

I am in the Junior Pioneers Under-Thirteens Football Team, but I am no Lev Yashin. Mostly, I play fourth reserve, because of my limping legs, which stop me running, so I get to carry the water bottles. I am good at biology but I am no Ivan Pavlov.

I am damaged. But only in my body. And mind. Not in my spirit, which is strong and unbroken.

When I was six-and-one-quarter years old I cross paths with worst luck. A milk truck smacks me from behind while I am crossing Yermilova Street. It sends me tum-bling somersaults through the air before bringing me down to earth, head first on the cobbles. Then a tram comes along, and runs me over, behind my back.

Things like this leave a lasting impression.

But Papa always encourages me to make the most of my misfortunities. He says ‘Every wall has a door’ and ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’

And whenever you complain to him, about anything – like injustice, weevils in porridge, getting punched on the nose at school, a broken leg, or losing fifty kopecks – he says, ‘Well, count yourself lucky. There are worse things in life.’

As it turns out, he’s three-quarters right. In time, all the bits of my head joined back together. Open wounds healed. Bones set. My legs mended, most parts. But there are some breaks in my brain, mostly in my thinking-departments, and without any clear memories of whatever came before.

I have some holes in my memory still. Sometimes I choose the wrong words. Or I can’t find the right one, and lay my hands on the real meanings. Facts fly out of my windows. My feelings can curdle like sour milk. Sense gets knotted. Then it’s hard to untangle my knowledge. I don’t concentrate easily.

Other times I cry for no good reason. Except I am throb-bing with sadness. Sometimes, I go dizzy and fall over. Then there are flashes of brilliant light – orange, gold and purple – and odd, nasty smells – like singed hair, pickled herring, carbolic, armpits and rotting lemons. Then I lose consciousness. They tell me I thrash about on the ground. And dribble frothy saliva. And ooze yellow snot through my nose. This is when I am having a fit. Afterwards I can’t remember any of it. But I have new bruises, which is a good thing, because it is my body’s way to remember for me what my brain has forgotten. Maybe I need to change my trousers, as a matter of urgency.

So I am sometimes slow and forgetful. Except in recreations and games – like battleships, hang-the-Fascist, chess and draughts – where I excel, because then everything I need to know lies seen, and open, there in front of me. So I can just play the game, without having to remember what happened on Thursday morning, how many sides on a dodecahedron, how to spell coccyx, or the Kapital of Uzbekistan.

So, overall, Papa tells me, the fool in me is finely balanced by my cleverness. And he calls me a pochemuchka. A child who asks too many questions. Without a brake on his mouth.

Plus I have another problem. It’s the unfortunate look of my face.

People keep staring at it. My face. And then start seeing things. That just aren’t there.

They gaze at me. They stare like an animal caught in headlights. Then they break into a smile. Then I smile back. Before you know it we’re talking. And, by then, we’re lost. It’s too late.

Papa says folk can’t help it. They see sympathy in my features. They find kindness in my eyes. They read friendliness in the split of my smiling mouth.

Guess what? They think I care about them. Even though they’re total, absolute, hundred-per-cent strangers. They think they know me. From somewhere. But they can’t remember where.

Papa says my appearance is a fraud and a bare-faced liar. He says that – although I am a good child in many ways, and kind enough – I am not half as good as my face pretends.

Papa says my face is one of those quirks of inheritance, when two ordinary parents can mix to produce something extreme and striking. You see it too with moths, orchids and axolotls.

He says my face is my very best, prize-winning quality. He says my smile is easy and wide. My features are neat and regular. My gaze is direct but gentle. It lends me a sweet and tender face. The very kindest face you’d hope to find. A face that seems to love whoever it looks upon.

Papa says it is a face that could have been painted by the Italian artist Sandro Botticelli, to show an angel on his best behaviour, sucking up to God.

It gives me grief, my sympathetic, wide-open, smiling face. Papa says I have a true genius for needless and reckless involvement in the private affairs of other people.

Also he observes I am foolhardy.

Beyond idiocy.

And that I talk without first thinking.

‘Shhh . . .’ he always says. ‘Idiot child.’

He says that when my head hit the cobbles of Yermilova Street, every fragment of fear got shaken out. Now my Frontal Lobes are empty, he says. My common sense went next. Closely followed by my tact, and then my inhibitions.

Of course, there’s a name for my condition. I suffer from impulsivity brought on by cerebral trauma. Which is a way of saying I talk a lot, and move a lot, and ask a lot of questions, and make up my mind quickly, and do things on the spur of the moment, and find new solutions to things, and say rude things without thinking, and interrupt people to tell them when they’ve got things wrong, and blurt things out, and change my mind, and make strange animal noises, and show lots of feelings, and get impatient, and act un-expectedly. All of which makes me like other people. But more so.

Because I make friends easily. With people and with animals. I enjoy talking. To anyone, more or less. And meeting new animals. Especially new species who I have never had the fortune to converse with before.

I like to help. Even strangers. After all, we are all chums and Comrades, put in this life to help each other, and rub along together.

In particular, I provoke whatever you call it when people-tell-you-too-much-about-themselves, even-though-it-is-secret-and-shameful, concerning-things-that-you-never wanted-or-expected-to-hear, and-are-probably-best-kept-secret, unspoken, for-all-concerned.

Like a confidence, but even worse.

A magnet attracts iron-filings. I attract confessions. Strongly. From all directions.

I only have to show my face in public and total strangers form an orderly line, like a kvass queue, to spill their secrets into my ears.

Soon, their honesties turn ugly.

‘I am a useless drunk.’ One says.

Or ‘I cheat on my wife, on Thursday afternoons, with Ludmilla, with the squint, from the paint depot, whose breasts smell of turpentine. By chance, she’s my brother’s wife . . .’

Or ‘I killed Igor Villodin. I hacked off his head with a spade . . .’

Or ‘It was me who stole the postage stamps from the safe in the bicycle-factory office . . .’

Often they flush with shame. Sometimes they start sobbing. They pull terrible gurning faces or gesture wildly with their hands.

Then I have to say, ‘I am sorry . . . but you are confusing me with my face. It’s much kinder than me, but it’s not to be trusted . . . Of course, I like you . . . But I cannot take on everyone’s problems. Not all the time. I have a young life of my own to live.’

‘Anyway,’ I say, ‘don’t worry. Things are never so bad as you imagine. Everything considered . . . What is done is done. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Every wall has a door. Make the most of your misfortunities. They make you what you are in life, and different from all other people. This is the only life you get. You must pick yourself up and move on.’

Aunt Natascha says everyone wants to confess in life, like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, because they need to be understood and find forgiveness somewhere.

And since Lenin did away with God, Praise the Lord, may he rest in peace, they must look elsewhere, and closer to home.

So, they pick on me.

I am twelve-and-a-half years old and I live in the staff apartments, in The Kapital Zoo, facing the sea-lions’ pool, behind the bisons’ paddock, next to the elephant enclosure, and I like to play the piano but I am no Sergei Rachmaninov because my right arm is crooked and stiff, so I mostly play one-handed pieces, such as are written for the army of one-armed veterans, who sacrificed a limb for the Mother-land, fighting in the Great Patriotic War.

I am in the Junior Pioneers Under-Thirteens Football Team, but I am no Lev Yashin. Mostly, I play fourth reserve, because of my limping legs, which stop me running, so I get to carry the water bottles. I am good at biology but I am no Ivan Pavlov.

I am damaged. But only in my body. And mind. Not in my spirit, which is strong and unbroken.

When I was six-and-one-quarter years old I cross paths with worst luck. A milk truck smacks me from behind while I am crossing Yermilova Street. It sends me tum-bling somersaults through the air before bringing me down to earth, head first on the cobbles. Then a tram comes along, and runs me over, behind my back.

Things like this leave a lasting impression.

But Papa always encourages me to make the most of my misfortunities. He says ‘Every wall has a door’ and ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’

And whenever you complain to him, about anything – like injustice, weevils in porridge, getting punched on the nose at school, a broken leg, or losing fifty kopecks – he says, ‘Well, count yourself lucky. There are worse things in life.’

As it turns out, he’s three-quarters right. In time, all the bits of my head joined back together. Open wounds healed. Bones set. My legs mended, most parts. But there are some breaks in my brain, mostly in my thinking-departments, and without any clear memories of whatever came before.

I have some holes in my memory still. Sometimes I choose the wrong words. Or I can’t find the right one, and lay my hands on the real meanings. Facts fly out of my windows. My feelings can curdle like sour milk. Sense gets knotted. Then it’s hard to untangle my knowledge. I don’t concentrate easily.

Other times I cry for no good reason. Except I am throb-bing with sadness. Sometimes, I go dizzy and fall over. Then there are flashes of brilliant light – orange, gold and purple – and odd, nasty smells – like singed hair, pickled herring, carbolic, armpits and rotting lemons. Then I lose consciousness. They tell me I thrash about on the ground. And dribble frothy saliva. And ooze yellow snot through my nose. This is when I am having a fit. Afterwards I can’t remember any of it. But I have new bruises, which is a good thing, because it is my body’s way to remember for me what my brain has forgotten. Maybe I need to change my trousers, as a matter of urgency.

So I am sometimes slow and forgetful. Except in recreations and games – like battleships, hang-the-Fascist, chess and draughts – where I excel, because then everything I need to know lies seen, and open, there in front of me. So I can just play the game, without having to remember what happened on Thursday morning, how many sides on a dodecahedron, how to spell coccyx, or the Kapital of Uzbekistan.

So, overall, Papa tells me, the fool in me is finely balanced by my cleverness. And he calls me a pochemuchka. A child who asks too many questions. Without a brake on his mouth.

Plus I have another problem. It’s the unfortunate look of my face.

People keep staring at it. My face. And then start seeing things. That just aren’t there.

They gaze at me. They stare like an animal caught in headlights. Then they break into a smile. Then I smile back. Before you know it we’re talking. And, by then, we’re lost. It’s too late.

Papa says folk can’t help it. They see sympathy in my features. They find kindness in my eyes. They read friendliness in the split of my smiling mouth.

Guess what? They think I care about them. Even though they’re total, absolute, hundred-per-cent strangers. They think they know me. From somewhere. But they can’t remember where.

Papa says my appearance is a fraud and a bare-faced liar. He says that – although I am a good child in many ways, and kind enough – I am not half as good as my face pretends.

Papa says my face is one of those quirks of inheritance, when two ordinary parents can mix to produce something extreme and striking. You see it too with moths, orchids and axolotls.

He says my face is my very best, prize-winning quality. He says my smile is easy and wide. My features are neat and regular. My gaze is direct but gentle. It lends me a sweet and tender face. The very kindest face you’d hope to find. A face that seems to love whoever it looks upon.

Papa says it is a face that could have been painted by the Italian artist Sandro Botticelli, to show an angel on his best behaviour, sucking up to God.

It gives me grief, my sympathetic, wide-open, smiling face. Papa says I have a true genius for needless and reckless involvement in the private affairs of other people.

Also he observes I am foolhardy.

Beyond idiocy.

And that I talk without first thinking.

‘Shhh . . .’ he always says. ‘Idiot child.’

He says that when my head hit the cobbles of Yermilova Street, every fragment of fear got shaken out. Now my Frontal Lobes are empty, he says. My common sense went next. Closely followed by my tact, and then my inhibitions.

Of course, there’s a name for my condition. I suffer from impulsivity brought on by cerebral trauma. Which is a way of saying I talk a lot, and move a lot, and ask a lot of questions, and make up my mind quickly, and do things on the spur of the moment, and find new solutions to things, and say rude things without thinking, and interrupt people to tell them when they’ve got things wrong, and blurt things out, and change my mind, and make strange animal noises, and show lots of feelings, and get impatient, and act un-expectedly. All of which makes me like other people. But more so.

Because I make friends easily. With people and with animals. I enjoy talking. To anyone, more or less. And meeting new animals. Especially new species who I have never had the fortune to converse with before.

I like to help. Even strangers. After all, we are all chums and Comrades, put in this life to help each other, and rub along together.

In particular, I provoke whatever you call it when people-tell-you-too-much-about-themselves, even-though-it-is-secret-and-shameful, concerning-things-that-you-never wanted-or-expected-to-hear, and-are-probably-best-kept-secret, unspoken, for-all-concerned.

Like a confidence, but even worse.

A magnet attracts iron-filings. I attract confessions. Strongly. From all directions.

I only have to show my face in public and total strangers form an orderly line, like a kvass queue, to spill their secrets into my ears.

Soon, their honesties turn ugly.

‘I am a useless drunk.’ One says.

Or ‘I cheat on my wife, on Thursday afternoons, with Ludmilla, with the squint, from the paint depot, whose breasts smell of turpentine. By chance, she’s my brother’s wife . . .’

Or ‘I killed Igor Villodin. I hacked off his head with a spade . . .’

Or ‘It was me who stole the postage stamps from the safe in the bicycle-factory office . . .’

Often they flush with shame. Sometimes they start sobbing. They pull terrible gurning faces or gesture wildly with their hands.

Then I have to say, ‘I am sorry . . . but you are confusing me with my face. It’s much kinder than me, but it’s not to be trusted . . . Of course, I like you . . . But I cannot take on everyone’s problems. Not all the time. I have a young life of my own to live.’

‘Anyway,’ I say, ‘don’t worry. Things are never so bad as you imagine. Everything considered . . . What is done is done. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Every wall has a door. Make the most of your misfortunities. They make you what you are in life, and different from all other people. This is the only life you get. You must pick yourself up and move on.’

Aunt Natascha says everyone wants to confess in life, like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, because they need to be understood and find forgiveness somewhere.

And since Lenin did away with God, Praise the Lord, may he rest in peace, they must look elsewhere, and closer to home.

So, they pick on me.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHamish Hamilton

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 0735233977

- ISBN 13 9780735233973

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages240

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 12.99

Shipping:

US$ 7.00

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Zoo

Published by

Hamish Hamilton

(2018)

ISBN 10: 0735233977

ISBN 13: 9780735233973

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. A Good Read ships from Toronto and Niagara Falls, NY - customers outside of North America please allow two to three weeks for delivery. ; 8.1889763696 X 5.5905511754 X 0.7874015740 inches; 240 pages. Seller Inventory # 149416

Buy New

US$ 12.99

Convert currency