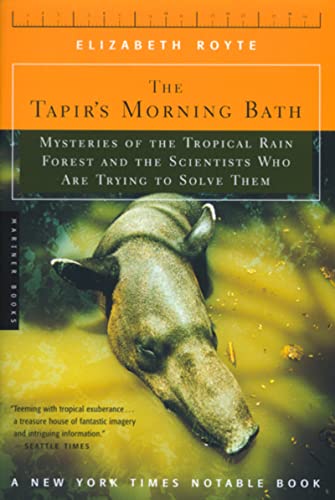

Items related to The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries...

In THE TAPIR'S MORNING BATH, Elizabeth Royte weaves together her own adventures on Barro Colorado with tales of researchers struggling to parse the intricate workings of the rain forest, the most complicated natural system on the planet. Through the lens of the field station, she also traces the history of modern biology from its earliest days of collection and classification through the decline of the naturalist to the days of intense niche specialization and rigorous scientific quantification.

As Royte counts seeds and sorts insects, collects monkey dung and radiotracks bats, she begins to wonder: what is the point of such arcane studies? The world over, rain forests are rapidly disappearing and species are going extinct. While humanizing the scientists in the field, she explores the tension between their research and the reality of a world that may not have time for the answers.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Lab in the Jungle

Gatun lake, the enormous midsection of the Panama Canal, sprawls for

thirty-seven kilometers around peninsulas of land, between fragments

of drowned mountains, and over the Continental Divide. Oceangoing

vessels slice through the canal and shudder into steel locks that

close and open almost silently. The lake"s shoreline is wildly

irregular, and its waters are as green as the sea.

Impenetrable forest flanks the canal. Toucans screech from

low branches, and monkeys leap from tree to tree. Iridescent blue

butterflies as large as teacup saucers flit along the shore. Inside

the forest, a dark tangle of creeping vines and fringed palms battles

to reach the sunlight. Here, where two continents meet and the waters

of two vast oceans lap against the lake, lies a teeming cornucopia of

life at its competitive extreme, a place like few others on Earth.

From a spot near the middle of Gatun Lake, opposite a

deserted village called Frijoles, Barro Colorado Island rises

steeply. Its muddy red banks appear jumbled, its interior black.

Isolated by the rising waters of the Chagres River, which was dammed

in 1910 to form the canal, Barro Colorado had been the highest point

on the Loma de Palenquilla ridge. Now the ridge is gone, and Barro

Colorado"s peninsulas and uplifts sprawl over 1,564 hectares, or six

square miles; its summit rises 119 meters above the lake"s surface.

From where I stood on the deck of the island"s launch as it

chugged through the shipping channel, I didn"t see Barro Colorado

until we were nearly upon it. Then, just before the place where the

canal arcs into Bohio Reach, I spotted several red and green channel

markers leading into a small cove. A swimming raft floated there.

Looking up, I caught a glimpse of tin-roofed dormitories set into the

fringed hillside. Emerging from the background of green was a flight

of steep concrete steps, which pulled my eye uphill to a graceful

veranda and, behind that, to a peaked roof almost lost in the

forest"s lush canopy.

The low-lying clouds of early morning draped the thickly

forested island, giving it the feel of a Chinese landscape painting.

Then a small motorboat puttered up to a dock. A woman in camouflage

pants tromped across a metal walkway. The lights flickered on in two

low-slung buildings. The laboratory in the jungle came to life.

This wasn"t my first visit to Barro Colorado. I had traveled to the

island nearly ten years before, in 1990, with the much-lauded Harvard

biologist Edward O. Wilson. He was there to collect Pheidole, the

largest genus of ants in the New World; I was there to write about

him for a magazine.

A hero to BCI"s residents, Wilson was charming and erudite.

He"d won two Pulitzer Prizes, for his writing on ants and on human

nature, and one Crafoord Prize, the ecologist"s equivalent of a

Nobel. He"d ushered the subdiscipline of sociobiology into the

mainstream, and now, in his sixties, he was lecturing world leaders

on the value of conserving biodiversity.

By day, Wilson and I had walked the forest trails. He"d

pointed out stingless bees and basilisks, foot-long lizards with

craggy fins down their back and tail. He"d explained the intricate

relationship between bruchid beetles and a large rodent called an

agouti. "Get a load of that," he would say effusively, without a

trace of self-consciousness, as he stooped to examine a cryptically

colored butterfly.

By night, we had sat around the table in the dining hall, the

building with the peaked roof and veranda that overlooked the cove.

Over plates of rice and beans a dozen scientists sparred and jousted.

They slung statistics and tried to best one another with observations

made in the rain forest. "I saw two howler monkeys copulating on

Fairchild Trail this morning," a serious-looking plant physiologist

said. "I almost stepped on a juvie boa constrictor," a bat researcher

countered.

After dinner we drank Atlas beers and the scientists griped

about how much money molecular biologists were taking from science

budgets, leaving the zoologists, the organismal biologists, the

ecologists, with nothing. Names were dropped, tenure decisions

criticized. Outside, the jungle thrummed and pulsed; inside, ants

streamed over a drop of grape jelly.

Most of the residents were male, with a bias toward

entomology. One was studying jumping spiders, another was looking at

the flight performance of migratory butterflies, another observed the

foraging patterns among leaf-cutter ants. One scientist spent her

days examining the teeth of dead anteaters; they offered clues to

evolution, she said.

From my first walk with Wilson, the forest had intrigued me.

But I found the island residents equally compelling. Like Wilson,

they focused on subjects that had seemed, to me, hopelessly arcane.

How do frogs produce their mating calls? How much water transpires

from a tree? Unlike Wilson, many of the scientists did nothing to

hide their ambition. They were often aggressive with one another, or

else painfully shy. Many had little social grace. That was fine by

me. After all, they lived in a jungle, and their struggle to survive,

to use the phrase made popular by Darwin, was tuned to fever pitch.

My first visit to Barro Colorado was brief, but I was there

long enough to see that its residents lived and breathed science

through their every waking hour. Their language was data, their

currency was scholarly publications, their religion was the creative

forces of nature itself. I didn"t understand a lot of what was going

on, but the work seemed important to me, and noble. At the time, the

word "biodiversity" was just beginning to enter the common parlance.

Rain forests were going up in smoke, and disappearing with them were

storehouses of knowledge and potential new drugs, foods, fuels, and

fibers. Scientists like Wilson were preaching the gospel of

conservation: every piece of the natural world, from microbes to

pandas, matters. Caught up in the excitement of this place, I trusted

that scientists like these would reveal, someday, exactly how.

When I got home from Panama, images of the rain forest stayed

with me, as did the patter of the postdoctoral students in the dining

hall and the roar of the insects outside my cabin door. Years passed.

Worldwide, natural areas continued to deteriorate. What was the role

of scientists now? At a time when so much was going wrong with the

environment, fewer people were being trained to know the environment.

There were fewer biologists who understood the relationships among

whole, living organisms or recognized individual species. Science

seemed ever more focused on molecular studies, on parsing genomes and

analyzing the expression of proteins. Eventually, I wondered, were we

going to lose touch with the world around us by being so fascinated

by the world inside us?

And yet in this world made smaller and narrower by

technology, researchers were still coming to BCI to make broad

studies without thought of profits or patents. They were studying

evolution in a forest, not in a test tube or a computer. It may sound

hokey, but there were still scientists on BCI who studied nature for

the pure joy of it. Their exuberance piqued my curiosity. And so,

three months before my own wedding, I said goodbye to my fiancé and

boarded a plane for Panama.

The island awoke at dawn with the desperate-sounding screams of a

thousand howler monkeys, bellowing their territorial yawp. The

toucans and parakeets and kiskadees were well up by now, ascreech and

atwitter. Bands of coatimundi, their ringed tails held aloft,

snuffled through the leaf litter of the lab clearing. In rubber

sandals that slapped against the concrete walkways, the scientists

slouched downhill toward breakfast.

I"d been here a day already, and I was eager to get into the

forest. Alone, I climbed the concrete steps that led away from the

lab clearing. Within the forest, the morning racket gradually settled

to a low hum of birds, insects, and frogs. An anonymous creature

obscured by the tangled understory let loose a sound like broken

ceramics in a bag. A chicken-sized bird produced an eerie wail --

like a finger circling the rim of a crystal glass.

Moving along the trail, I stepped over ants carrying bright

green leaf fragments. I stared at a pattern of brown-dappled light

that beamed across the forest floor. It slithered away when I

approached -- a five-foot boa constrictor with no taste for

confrontation.

The forest was greenly dim. The air smelled of dampness, of

earth, of mammals. A branch snapped above my head, but no pieces made

it through the snarl of vines, saplings, and shrubs to reach the

ground. I came upon a fig tree, its bark smooth and its trunk skirted

with enormous buttresses. The renowned scientific traveler Henry

Walter Bates, working his way through Amazonia in the middle of the

nineteenth century, compared these buttress chambers to stalls in a

stable, some of them large enough to hold a dozen people.

Woody vines called lianas looped over the forest floor like

cursive writing run amok. Grasping neighbor trees with their

tendrils, thorns, hooks, arboreal roots, and leader shoots, they

hoisted themselves into the canopy, where they lounged over the

treetops and sprawled for hundreds of meters. Their stems, meanwhile,

grew as thick as many a temperate tree. Examining the fresh tips of

one vine, I thought that if only I could sit still for two hours I"d

certainly see them grow.

But it was too hot to stay in one place, and soon I moved on,

turning from Wheeler Trail onto Barbour-Lathrop. A twenty-centimeter

seedpod covered with thousands of tiny spikes caught my eye. A spider

disguised as white rootlets lay flat against a tree trunk. A blue

morpho with a fifteen-centimeter wingspan flopped by in the soggy

air, headed downhill toward a sunlit creek. With its arresting

coloration and outsize proportions, this butterfly seemed the

quintessential symbol of biological weirdness spawned by the hothouse

climate. Here things got large, even unseemly: flower petals the size

of cake plates, beetles like grenades, leaves as long as coffee

tables.

The morpho alit on a tree trunk, folded its wings, and

instantly disappeared, its underwing coloration a perfect crypsis

against the mottled bark. This was nature, I thought, at the height

of her creative powers.

Charles Darwin knew intuitively that tropical forests were places of

tremendous intricacy and energy. He and his cohort of scientific

naturalists were awed by the beauty of the Neotropics, where they

collected tens of thousands of species new to science. But they

couldn"t have guessed at the complete contents of the rain forest,

and they had no idea of its value to humankind. Even now, more than a

century later, the mechanisms of the rain forest still baffle, and

impress, scientific thinkers.

Some of the best of them have worked on Barro Colorado

Island. The laboratory on the island"s northeastern shore has

operated continuously since 1923, its backyard the most-studied

tropical rain forest in the world. Barro Colorado is both a monument

of nature and, perhaps more tellingly, a monument to nature -- off-

limits to the general public, virtually stateless. Sitting between

two continents, it is populated by field researchers from around the

world and administered by the Smithsonian Institution, which acts as

a diplomatic mission to science.

The station was the brainchild of James Zetek, a U.S.

Department of Agriculture entomologist who"d been working on mosquito

control in the Canal Zone since 1909. Zetek, a Czech from Nebraska,

had noted the ongoing destruction of the local watershed: land that

had been forested was being logged and farmed for the simple reason

that it was now, via the canal"s labyrinthine shoreline, reachable.

Zetek took every opportunity to speak with scientists who

passed through the Zone about setting aside land as a "natural park,"

but it wasn"t until March 1923 that he got lucky. He met up with

William Morton Wheeler, a professor of economic entomology at

Harvard"s Bussey Institute for Research in Applied Biology, and took

him by train to the tiny lakeside town of Frijoles, from which point

a boatman ferried the men to Barro Colorado.

Wheeler spent just an hour on the island, but in a clearing

of less than one acre he collected nineteen species of ants. Zetek

took ten species of termites, and each of them took a dozen species

of myrmecophiles and termitophiles. "Two new genera, one a beetle,

very remarkable!" Wheeler would later write.

Zetek made a similar pitch to Thomas Barbour, the associate

curator of reptiles and amphibians at Harvard"s Museum of Comparative

Zoology, who was also conducting research in Panama that month.

Together they decided that BCI, the only large piece of relatively

undisturbed virgin forest left in the Canal Zone, would make an ideal

place to conduct biological research.

Seeking protection from settlers, hunting, and other human

interference, Zetek presented his idea to the Canal Zone"s governor,

Jay Johnson Morrow, who received it warmly. With an alacrity unheard

of in the modern conservation era, Morrow proclaimed the island a

nature reserve on April 17, 1923. From this day on, settlers would

decamp; any hunters who were found trespassing would be considered

poachers.

Unfortunately, Morrow had no funding for the station, and

neither did the U.S. government. The men who dreamed of a field

station would have to build it themselves. Barbour had recently made

a killing on the stock market and was willing to help out. David

Fairchild, the U.S. Department of Agriculture"s chief "plant

explorer," gave his own money (his wife was the daughter of Alexander

Graham Bell) and raised even more from his socialite friends Allison

Armour and Barbour Lathrop. Their money put up buildings and a track

and engine to hoist supplies, by cart, up the 196 concrete steps

between the lake and the clearing.

It was here that the laboratory rose. Facing northeast, the

wood-frame building afforded excellent views out over the lake,

toward the jumbled green hills in the middle distance and, on a clear

day, on to the low spine of the Cordillera, the backbone of Panama"s

uplift.

On my second trip to the island I was happy to see the old lab still

standing, though substantially reconfigured; it looked trim and

neatly painted. I"d eaten in the downstairs dining room ten years

before, but the building was now used as a visitor"s center and a

party hall. Since a wave of renovations in the early 1990s, everyone

ate in a new building farther downslope. The scientists worked in air-

conditioned labs near the lakeshore and slept in relatively insect-

free dorms built of poured concrete.

Beyond the lab clearing, though, everything seemed the same --

as ten years earlier, or a hundred. The island was still thickly

forested, and there were still no roads or villages. Evidence of

modernity was scant. History looped all around me in the fifty-nine-

kilometer trail system.

Turning off Bar...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMariner Books

- Publication date2002

- ISBN 10 0618257586

- ISBN 13 9780618257584

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Tapirs Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 521PY6001XRY

Tapir's Morning Bath : Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest and the Scientists Who Are Trying to Solve Them

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 729424-n

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest and the Scientists Who Are Trying to Solve Them (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. The Tapir's Morning Bath: Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest and the Scientists Who Are Trying to Solve Them 0.96. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780618257584

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0618257586-2-1

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0618257586-new

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2416190080112

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0618257586

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0618257586

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Solving the Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0618257586

Tapir's Morning Bath Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest and the Scientists Who Are Trying to Solve Them

Book Description PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. THIS BOOK IS PRINTED ON DEMAND. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # IQ-9780618257584